Coronavirus Downturn vs. Global Financial Crisis

When the coronavirus crisis first hit, many optimistically predicted a rapid economic rebound in the second half of the year. The outlook has since darkened, with rising fears of widespread bankruptcies, sovereign defaults, long-term unemployment, and a slow and painful recovery. In many ways, what started as a short and sharp external shock is slowly turning into the type of prolonged pain last experienced during the global financial crisis (GFC). As the world grapples with its second devastating downturn in just over a decade, what lessons does the past hold for today’s policymakers?

Early forecasts of the economic impact of the coronavirus dramatically underestimated the magnitude of the disaster, which dwarfs that of the GFC.

Some early forecasters estimated the loss of up to three million jobs in the US. Over the eight weeks between March 21 and May 9, however, over 36 million Americans filed for unemployment and Labor Department unemployment numbers showed 20 million jobs lost in April alone. In contrast, US job losses in the wake of the GFC amounted to around 9 million over a period of several years.

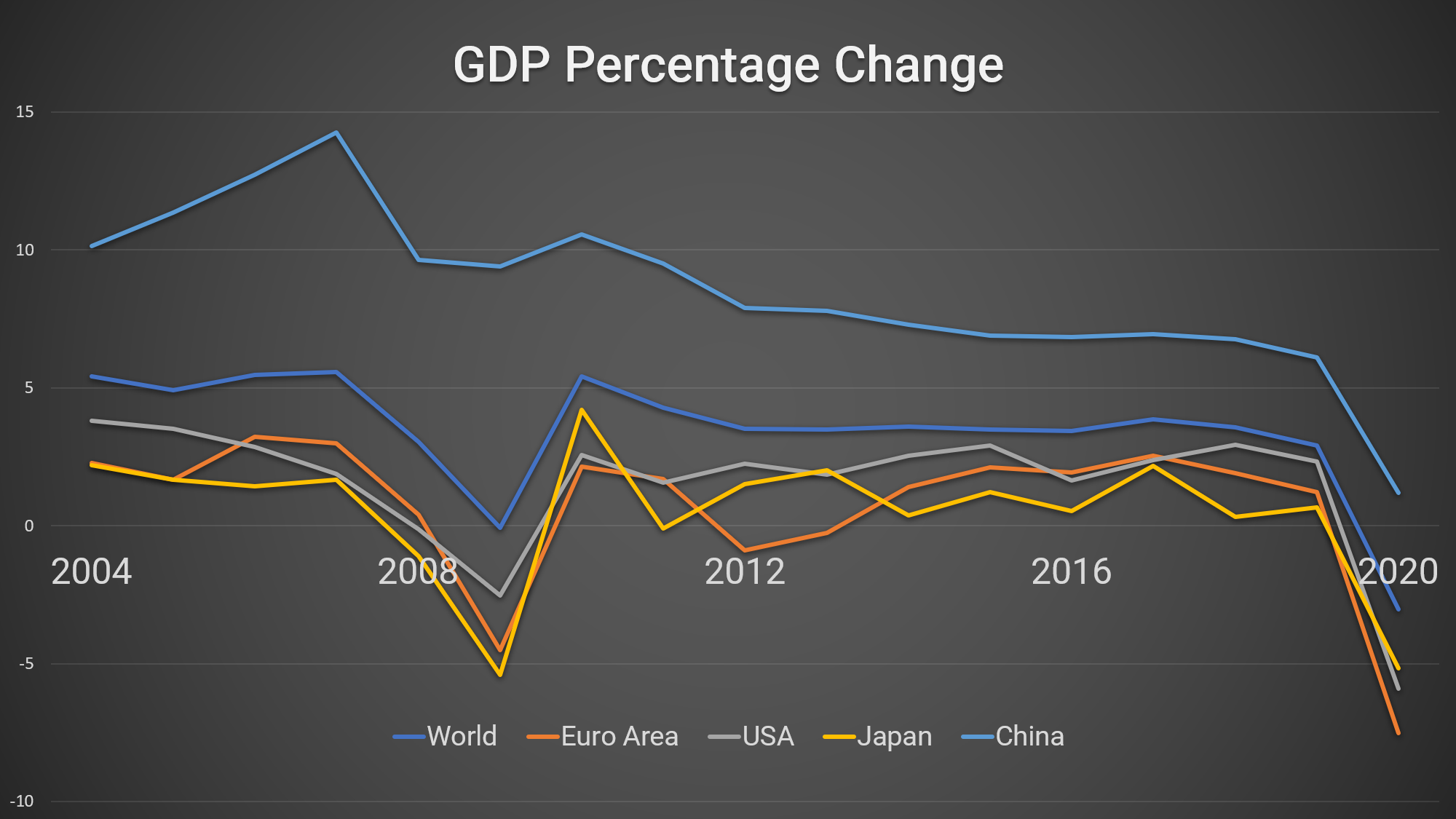

Similarly, in March, Bloomberg Economics projected a worst-case scenario of zero global growth in 2020. By mid-April, the International Monetary Fund (IMF) was predicting the world economy would shrink by 3% in 2020, far worse than the 0.7% annual contraction experienced at the height of the previous crisis in 2009.

Barely ten years after the world was ravaged by the GFC and subsequent recession, then, we are facing the most significant economic shock since perhaps the Great Depression.

As policymakers scramble to undo the damage, what are some of the similarities and differences between this century’s two biggest economic crises and what lessons can we learn from the past?

IMF. World Economic Outlook, April 2020. 2020 figure is an estimate.

Key differences

One key difference between the GFC and the coronavirus crisis is that the GFC was the result of an endogenous shock while the coronavirus crisis was born of an exogenous shock.

Endogenous shocks originate from within the system. In the case of the GFC, it is generally accepted that the troubles started in the US mortgage market. Risk accumulated in that market as credit standards declined, and when those risks began to unwind, the world faced a massive credit crisis. Financial markets froze, liquidity dried up, and a painful recession resulted.

Exogenous shocks originate from outside the system, like a meteor striking the earth. The coronavirus is a classic exogenous shock – a public health crisis that arose unexpectedly and precipitated a global collapse in both supply and demand.

Another difference is that, in contrast to the previous crisis, the financial system started the year in reasonably good health. Bank prudential regulation was overhauled after the GFC and today, banks are better capitalized than they were in 2007. In addition, new rules have meant that a larger proportion of high-risk lending is done by nonbank institutions, including hedge funds, sovereign wealth funds, bond markets, and others. Thus, banks are less exposed to risk than they were previously, which is positive for financial stability.

From a historical perspective, this is all good news. Most serious financial crises have resulted from endogenous issues such as mispriced risk, extreme maturity mismatches, regulatory arbitrage, and problems in off-balance sheet liabilities. In the past, crises precipitated by exogenous shocks have been quickly absorbed by healthy financial systems, with growth resuming smoothly once the disruption ended. This is why many experts anticipated that economies would bounce back quickly once the coronavirus threat ends.

Seeds of a credit crisis

Unfortunately, hopes for a fast recovery have dimmed and there is a growing risk that the exogenous shock of the coronavirus will trigger endogenous troubles in debt markets.

In 2008, central banks rushed to support liquidity amidst the credit crisis. Then, in the face of a slow recovery, they held interest rates at historically low levels for over a decade in an attempt to stimulate economic growth.

Related Tutorial: Monetary Policy Analysis

This has had the effect of dramatically increasing global debt levels. Sovereign and corporate debt burdens have grown rapidly, and the average quality of corporate bonds has declined. As credit rating agencies (CRAs) have noted, covenants protecting investors have increasingly been cut from bond issues.

While credit markets have been broadly stable during the current crisis – thanks to massive efforts by global central banks, particularly the US Federal Reserve – there have been bouts of troubling market activity.

Emerging market (EM) bonds, for example, saw their yields spike in April before interventions by the IMF eased – perhaps temporarily – fears of EM sovereign defaults. Similarly, corporate bond markets have flashed warning signals – The Economist reports that debt downgrades are accelerating as CRAs reevaluate the outlook for businesses that have seen revenues plunge. Even US Treasury markets experienced disruption before Fed intervention smoothed trading.

Should the coronavirus crisis be prolonged, either due to extended lockdowns or a second wave of infections, both corporate and sovereign defaults will inevitably rise. This may lead to a credit crisis that central banks will be hard-pressed to address after years of quantitative easing (QE).

Oil

Further complicating the global picture, oil markets have been behaving unusually. Global oil demand has plunged, and surplus storage capacity is rapidly filling up. At the same time, Russia and Saudi Arabia have engaged in an ill-timed price war. This has sent oil prices plunging and thrown the US oil industry into disarray. The benchmark West Texas Intermediate (WTI) price per barrel briefly turned negative and bankruptcies are rising fast among US producers.

These disruptions threaten future investment and growth. Even if coronavirus lockdowns lift, a slow recovery, oversupply, and built-up reserves could restrain oil price growth for months.

Lessons learned

The silver lining to the gloomy economic picture is that many governments appear to have learned lessons from the GFC. Central banks have been quick to roll out emergency measures, including lower interest rates, significant bond-buying programs, and other QE measures.

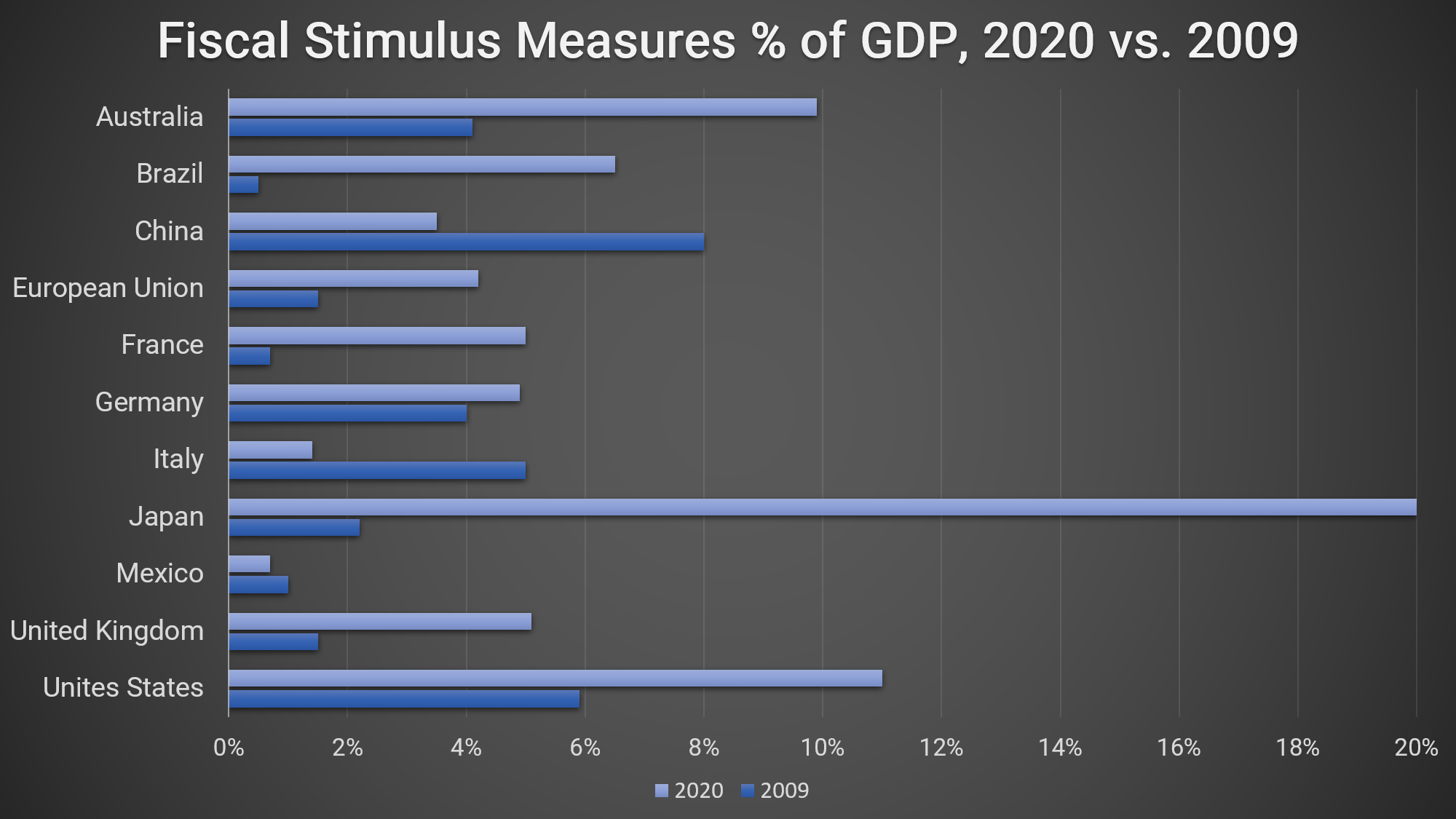

At the same time, governments have been quick to enact emergency fiscal stimulus measures. In contrast to the GFC, when fiscal measures were limited and relatively small, most national governments have rolled out generous fiscal packages in a bid to offset the economic damage caused by sudden lockdowns.

In most countries, these packages exceed those enacted in 2009. However, there is a key exception to this – China. In 2009, China rolled out the world’s largest fiscal stimulus as a percentage of GDP. This time, however, China’s program is significantly more modest than those of other countries. This is likely due to Chinese uncertainty about its domestic outlook amid ongoing coronavirus outbreaks and its high levels of debt.

Atlantic Council. G20 Covid-19 Response. April 2020.

In the wake of the GFC, Chinese fiscal measures and economic activity helped lift the whole global economy and China has acted as the global engine for growth over the last decade. Today, its reluctance to enact major measures suggests that it will not play the same role in the recovery from the coronavirus crisis. With constrained growth prospects across Europe and North America, this bodes ill for the future.

Intuition Know-How has a number of tutorials that are relevant to the global financial crisis and other topics discussed above:

- Global Financial Crisis – Causes, Impact, & Legacy

- Business Cycles – An Introduction

- Monetary Policy Analysis

- Fiscal Policy Analysis

- Financial Regulation – An Introduction

- Financial Authorities (US) – Federal Reserve

- Financial Authorities (UK) – Bank of England

- Financial Authorities (Europe) – ECB

- Fixed Income Analysis – Credit Risk