Fossil fuels and net zero – can they ever be compatible?

The road to net zero is a complicated journey with multiple diversions, forks, and confusing terrain, not least exemplified by the contention that it can be achieved while actually increasing fossil fuel production.

Climate change objectives are typically articulated in terms of a target date for achieving net-zero greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions, linked to the peak global temperature increases set out by the 2015 Paris Agreement. This aims to limit global warming to well-below 2°C above pre-industrial levels and to pursue efforts to limit it to 1.5°C.

The recent decision by UK Prime Minister Rishi Sunak to allow more oil and gas drilling in the North Sea while simultaneously reaffirming his party’s pledge to cut carbon emissions to net zero by 2050 has focused attention on what may – and may not – qualify as legitimate tactics on the road to net zero.

Mr. Sunak sees no inherent contradiction between these two apparently opposing stances. For many, his statement on new drilling is a transparently opportunistic political maneuver as his party seeks to appease and appeal to climate change sceptics. Nonetheless, the defense of his position highlights the question as to whether there can ever be space for fossil fuels in the net-zero transition.

Rishi Sunak, UK Prime Minister, who has decided to allow more oil and gas drilling in the North Sea (Source: Politico.eu)

Carbon capture and storage justifies fossil fuel production

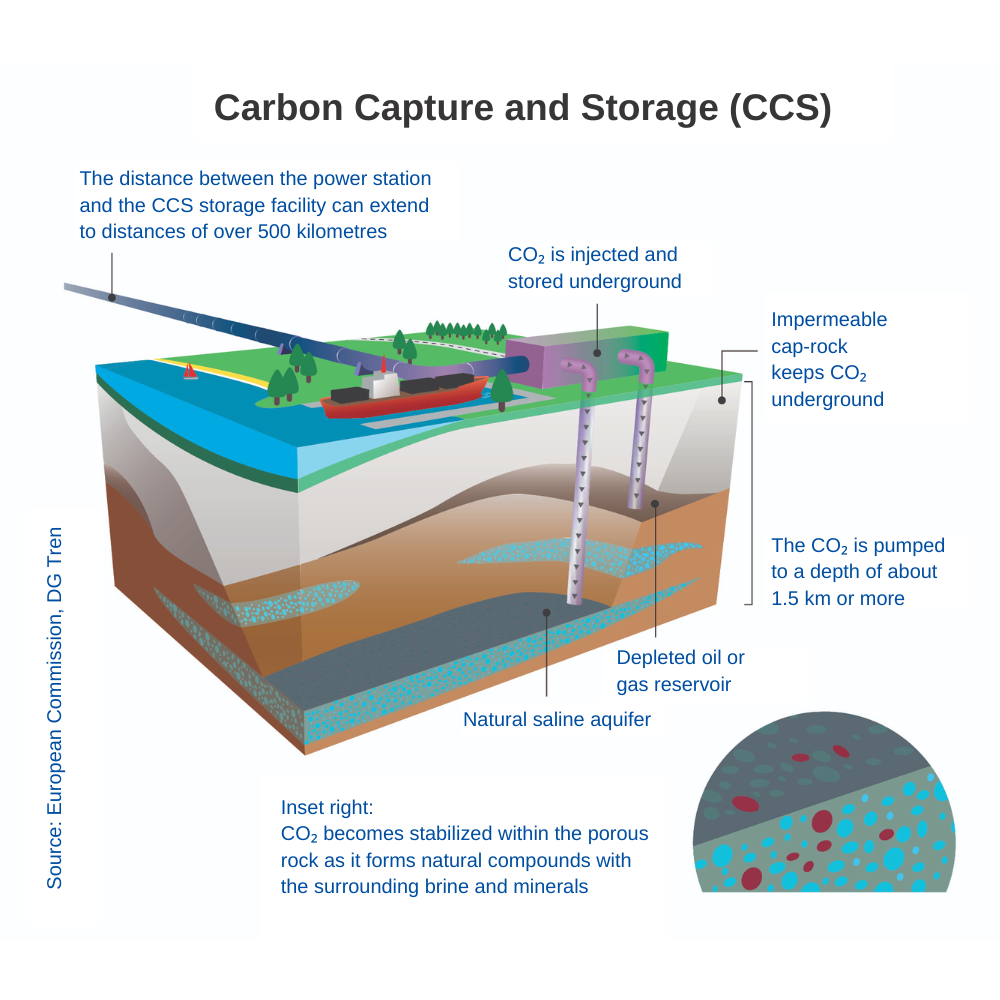

The UK Prime Minister sought to justify the expansion of drilling by announcing simultaneously government support for two new carbon capture and storage (CCS) schemes. The capture of carbon dioxide emissions from industrial processes, including oil refining, and its planned storage in disused North Sea wells, is central to the UK’s commitment to reach net zero by 2050. Indeed, it intends to continue to transition from fossil fuels after that date with CCS technology a critical part in its justification.

[Green bonds explained and the different types of green asset]

A recent report from the International Panel for Climate Change (IPCC) – and other research – would seem to offer Mr. Sunak some comfort in relation to continued fossil fuel emissions. Because renewable energy sources such as solar and wind power are intermittent, there is an argument that these need to be backed by traditional energy sources that may be called upon when the sun fails to shine and the wind dies down – but there is plenty of alternative research that contends that these shortcomings are close to being resolved through advancements in technology.

There is also the contention that as natural gas releases roughly half the carbon dioxide emissions as coal, so transitioning from coal to natural gas cuts down on CO2 emissions. At the same time, some research asserts that natural gas emissions are hugely underestimated.

[Biodiversity explained: What is its impact on the finance industry?]

CCS technology is still unreliable at scale

And so it is the area of carbon capture where the battleground lies. The IPCC contends that pairing natural gas and other fossil fuels with CCS and elimination of methane leaks could render these fuels low-to-zero emissions. But while carbon capture is central to every net zero scenario, even the IPCC admits that CCS technology is unproven at scale and unreliable as a means to limit global warming to 1.5°C. Hence, for many, CCS is simply a smokescreen for fossil fuel companies to retain the status quo indefinitely.

Two types of carbon credits

The potential for CCS to make a meaningful contribution toward net zero is tightly bound to carbon markets and in particular the pricing of carbon credits. A carbon credit is an emissions unit that is issued by a carbon crediting scheme and represents a reduction or removal of GHG emissions. There are two major types. Avoidance credits are generated from renewable energy or forest conservation projects (but don’t actually remove carbon from the atmosphere). Removal credits, meanwhile, are generated by projects that remove CO2 directly from the atmosphere.

Carbon markets and the threat to net zero

And there are two types of carbon markets. In compliance-led carbon markets, such as the EU Emissions Trading Scheme (EU ETS), governments impose a regulatory cap on emissions for specific industries. If these are exceeded, allowances for excess emissions must be purchased in the market, where unused allowances may also be sold. In voluntary carbon markets, emitters can voluntarily buy carbon offsets. These are certified and compensate for their emissions.

Right now, the UK’s position on carbon pricing is also contentious and highlights issues around the role of carbon pricing in shaping net-zero policy. Specifically, by offering more carbon allowances and relaxed emissions reduction targets for polluters, the UK carbon price (under the UK Emissions Trading Scheme) is now nearly half that of its EU equivalent. The integrity of carbon markets has already been called into question by carbon credit projects allegedly exaggerating their emissions reductions. Underpricing of carbon credits likewise has potential to frustrate net-zero aspirations.

Intuition Know-How has a number of tutorials relevant to the content of this article:

-

Climate Risk – An Introduction

- Climate Risk Measurement – An Introduction

- Climate Risk Measurement – Approaches

- Climate Risk – Banking & Decarbonization

- Climate Risk – Stress Testing

- Commodities – An Introduction

- Commodities – Crude Oil

- Commodities – Oil Products

- Commodities – Natural Gas

- Commodities – LNG

- Commodities – Coal

- Commodities – Renewables

- Commodities – Emissions