Figure out your learning model

Models and theories offer us frameworks for thinking. As a society we use them for pondering everything from astrophysics to GDP growth. A theory or model explains how something works. No one model will ever be one hundred per cent accurate in every situation, however, many of them can be very useful.

The same applies when we talk about learning. Having a mental model of how and what happens when we learn, can guide us when it comes to designing our learning programs. Understanding the various elements within these theories and models forces us to think clearly, rationally, and productively about creating learning.

***

This is the second article in a four part series which briefly describes how we go about the design of our learning. It gives an insight into some of the principles and practices that inform what we do. You can access the other 3 articles below:

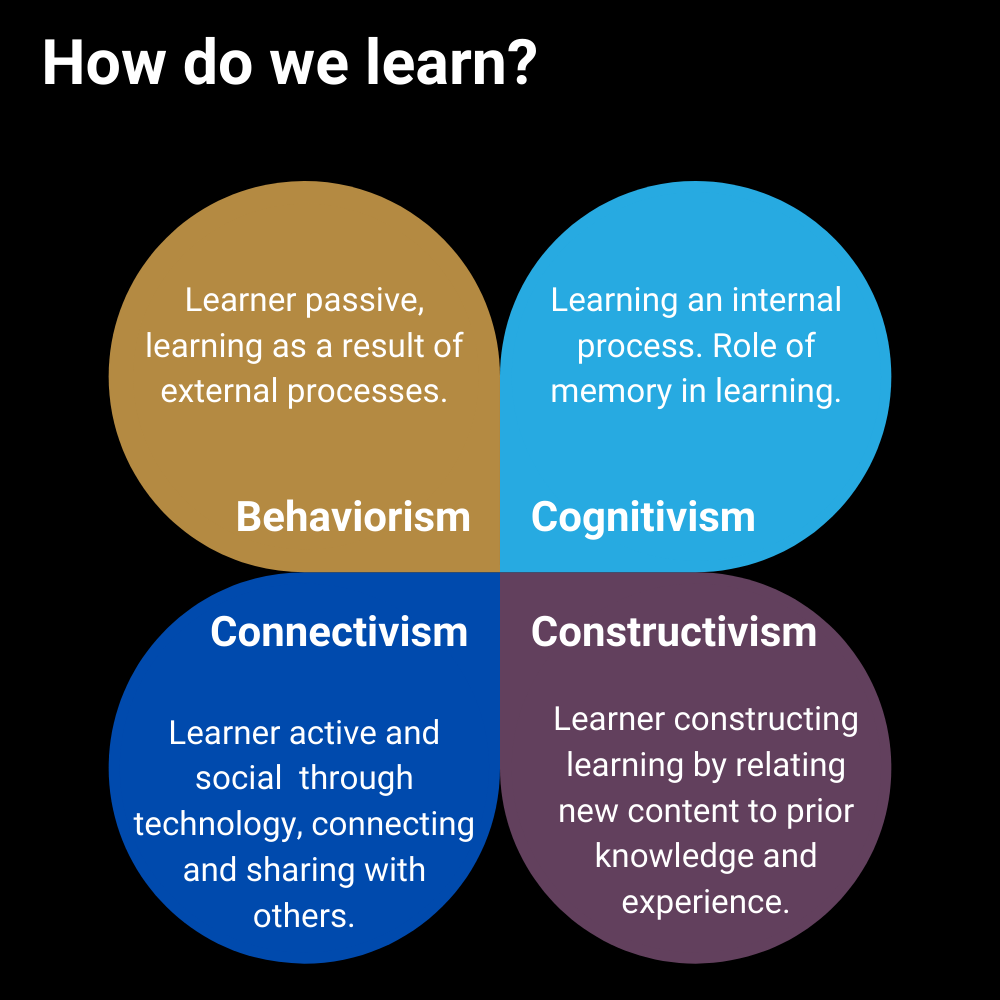

Design thinking challenges us to understand the perspective of our learners intimately, but thinking about how we think about learning is equally important. Anyone involved in education is probably familiar with theories like Behaviorism, Cognitivism, Constructivism and Connectivism at a minimum. Working in instructional design, people also hear a lot about Bloom’s Taxonomy or Mayer’s work on multi-modal learning.

These theories and models attempt to explain how and why we do things, what factors are important in learning, for example from a brain biology point of view, the ability to pay attention, form memories, become emotionally affected, make decisions and manage our learning, all impact our ability to learn.

Theory and thinking around learning has been developing for over one hundred and twenty five years and while many principles from certain schools of thoughts are still relevant, our own learning model in Intuition orbits around Constructivism, whereby learning is a continuous process of constructing or meaning making. Learners interact with experiences and construct knowledge, develop skills in a generally self–directed mode, guided by appropriate levels of facilitation. One important feature of this way of thinking, is that the focus is on the learner more than the teacher. Even today, a misbelief still holds sway, that it’s all about the teaching, that teaching will always cause learning and that putting the content up, or presenting the material, providing the links and access, developing the content is the most important task. While this is of course important, this remains a teacher focused perspective. It does not serve our learners well.

The strategies we use are designed to engage our learners in an active learning process, where they can connect their learning, relate new material to prior knowledge and construct meaning from the learning experience.

Lastly, we support the finding that working memory is extremely limited, while long term memory is essentially limitless. So, we constantly work to minimize cognitive load¹ during learning while helping our learners engage with content in ways that help them encode and remember it.

Learning made for adults

Learning is complex. We use the word ‘learn’ in many ways: to learn to ride a bike, learn a new language, learn about an event (i.e. hear about) and learn new skills and capabilities. Our learning design targets this fuzziness, by drawing inspiration from evidence-based research. We make learning for adults who are agile and task driven, yet time poor and pressurized.

In recent years, neuroscience has provided some insights to help guide our approach to learning. While there is still some debate about how much neuroscience research can flow directly into useful educational practice, it is a knowledge space worth tracking. John Medina, author of Brain Rules[1] highlights several key principles that inform our design:

- Learners do not pay attention to boring things

- A multi-sensory experience optimizes learning while vision trumps all senses

- Humans are powerful and natural explorers

- Repeat to remember

Medina points out how our brains haven’t changed a great deal since earliest times. Our brains are hardwired for sensory input, sound, sight, touch, hearing and taste. We evolved and our senses evolved working in unison. Vision trumps all other senses and the more senses stimulated the better the learning. If possible learning, link sense, audio and visual.

We believe that neuroscience is an area growing in relevance and coverage; educational psychology can be enhanced and extended by what we’re learning about the human brain.

Another research area becoming increasingly relevant to learning is the role of emotion. For example, if we really want to trigger memories and take-aways, then learning design should seek to trigger dopamine and oxytocin ̶ neurotransmitters that trigger positive emotions. Emotions matter, how we feel, how a learning experience makes us feel, ultimately helps us encode something more deeply.

Models and theories give us mental models to think about learning. But no one model will contain the complete truth. Models tend to build on top of previous models, evolving and shifting as new information and science comes to light debunking older ways of thinking. With each passing year, new data and new developments point us in fresh directions.

Keeping abreast of such advances in the relevant sciences of educational and cognitive psychology and neuroscience is important. Referencing a variety of models in a toolkit of thinking offers a genuinely holistic approach to learning and when this is informed by the practical experience of what actually works within training and development in organizations, then we arrive at well informed learning program design.

Be informed and let that inform our design. Apply the common-sense knowledge (often not that common) of what actually works. As educators we owe this to learners.

[1] John Medina (2014), Brain Rules